A worldwide campaign of assassinations of Hamas leaders announced by senior Israel officials is likely to be counterproductive, impractical and ineffective, targets of previous such efforts have suggested.

Benjamin Netanyahu first announced the new strategy two weeks after the 7 October attacks launched by Hamas into southern Israel which killed 1,200 people.

Officials in Israel have briefed journalists that a new operation called Nili, an acronym for a biblical phrase in Hebrew meaning “the eternal one of Israel will not lie”, would target senior leaders of the militant Islamist organisation.

Last month Netanyahu told a press conference that he had instructed Mossad, Israel’s overseas intelligence service, to “assassinate all the leaders of Hamas wherever they are”. In early December a leaked recording revealed Ronen Bar, the head of Shin Bet, Israel’s internal security agency, telling Israeli parliamentarians that Hamas leaders would be killed “in Gaza, in the West Bank, in Lebanon, in Turkey, in Qatar, everywhere … It will take a few years, but we will be there in order to do it.”

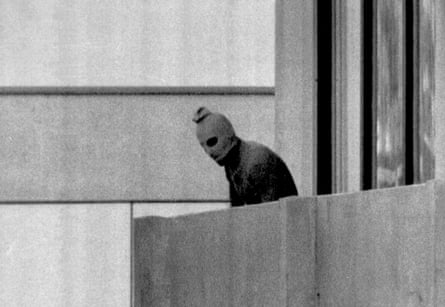

Bar described the assassination campaign as “our Munich”, a reference to the campaign launched by Israel after the attack by Palestinian extremists on the Munich Olympics in 1972 that killed 11 Israeli sportsmen. That effort led to at least 10 assassinations between December 1972 and 1979, and was portrayed in the Steven Spielberg film Munich. Since then, Israel has conducted dozens more clandestine assassinations, with targets ranging from Palestinian leaders to Iranian nuclear scientists.

A group of Palestinian gunmen held Israeli athletes hostage in a 20-hour standoff at the Munich Olympic Village in 1972; 11 of the athletes, five of the Palestinians and a German policeman died. Photograph: Kurt Strumpf/AP

Currently, Israeli security services are focused on killing the leaders of Hamas in Gaza, analysts said. The Israeli military has said it is closing in on Yahya Sinwar, the suspected architect of the 7 October attacks, after a months-long offensive that has devastated swaths of the enclave and killed more than 20,000 people, the majority civilians, according to the Hamas-run health authorities there.

But the announced campaign has a much broader scope, potentially targeting leaders of Hamas based in Qatar, Turkey, Lebanon and the group’s support networks elsewhere.

“We understand that we have to … reach everyone in the [Hamas] leadership … because we will not paralyse this organisation without eliminating these very influential figures. They were deeply implicated in the murderous attack of October 7 and must pay the price,” said Prof Kobi Michael, a senior researcher at the Institute for National Security Studies in Tel Aviv.

But not all are convinced by such operations. Yossi Melman, a journalist and author who has covered the Israeli security services for decades, said the assassinations strategy “doesn’t solve anything”.

“The Israeli intelligence community is in love with assassinations, and now they are ashamed, humiliated and they want to redeem themselves,” he said.

The Israeli military has said it was closing in on Yahya Sinwar, the head of Hamas. Photograph: Sopa Images/LightRocket/Getty Images

Others have suggested that the repeated public references to the campaign expressed a desire among officials to reassure a fearful population that has lost faith in the ability of Israel’s vaunted security services and government to keep them safe.

“It’s looking a bit like sensationalism. It’s fun to recall what happened after Munich, but not relevant, really, unless Hamas manage to flee the Gaza Strip and make their way to countries where we can track them down, and that’s unlikely to happen,” Yossi Alpher, a Mossad official in the 1970s, said. “What we did back then was all over Europe and we did it clandestinely. We eliminated someone and got away with it.”

Some historians have questioned whether Mossad’s assassination campaign after Munich targeted those actually involved in the attack on the Olympics, and have suggested that it may have been counterproductive in the long run.

Fathi Shaqaqi, the founder of the Palestine Islamic Jihad group, was killed in Malta in 1995. Photograph: Ahmed Jadallah/Reuters

But some assassinations by Israel have had a real strategic effect, experts said, citing the examples of Fathi Shaqaqi, the founder of the Palestine Islamic Jihad (PIJ) group, who was killed by Mossad in Malta in 1995, and Imad Mughniyeh, a key organiser of terrorist attacks by Hezbollah, the Lebanon-based Islamist militia and political movement, who was killed by Mossad and the CIA in a joint operation in 2008. Shaqaqi’s death crippled PIJ for some years, and Mughniyeh’s was a major blow to Hezbollah.

But PIJ rebuilt its strength in the years that followed Shaqaqi’s death, and took part in the 7 October attacks. That operation’s overall masterminds were a new generation of Hamas leaders who rose to power following the assassinations by Israel of its most senior leaders 20 years ago.

“We killed the founder of PIJ and we killed the founder of Hamas [in 2004]. Even when there is a genuine strategic effect, such as with the killing of Mughniyeh, it is not enduring … Hezbollah is still alive and kicking,” said Melman.

The Hezbollah leader Imad Mughniyeh was killed in a joint operation by the Mossad and the CIA in 2008. Photograph: Ramzi Haidar/AFP/Getty Images

Nor does assassination necessarily act as a deterrent, a key aim of such campaigns.

The Guardian interviewed five Palestinians targeted by assassination operations over more than 50 years. All said the attempts on their lives by Israeli intelligence services merely strengthened their convictions and helped recruitment to their factions.

Bassem Abu Sharif, who was badly injured in 1972 by a bomb sent by Israel, recalled how he had received a package at the Beirut offices of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), a group responsible for a series of international hijackings of Israeli and other planes as well as attacks into Israel. Abu Sharif’s predecessor as its spokesperson, the intellectual and activist Ghassan Kanafani, had been assassinated by Israel shortly before.

“The package was addressed to me and … there was a book on Che Guevara inside … I opened the book, and turned over three pages and I saw the explosives linked to a battery,” Abu Sharif remembered.

Then 26, he underwent nine hours of surgery but remained maimed for life. “They took my finger; they took my eye and 65% of the sight in the other one; I can’t smell, I can’t taste. They destroyed it.”

Abu Sharif said the attack made him more determined than ever to continue his activism with the PFLP. He was active through the rest of the decade and eventually became a key adviser to Yasser Arafat, chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organisation.

“I never had fear in my heart. I never hesitated to do a mission, even the most dangerous,” he told the Guardian at his home in Jericho.

The campaign that followed the Munich attacks slowed but did not stop after the killing of a Moroccan waiter in Norway who was mistaken for one of the Mossad’s highest-priority targets, Ali Hassan Salameh, a senior security official in the Fatah armed faction. He eventually died in 1979 in a car bombing by Mossad in Beirut.

Tawfiq Tirawi, a former Fatah intelligence chief active in the 1970s, said the group had fought back, killing a Mossad agent and badly injuring another. An Israeli diplomat in London also died after opening a letter bomb.

“In fact, there was an exchange of assassinations between us and the Israelis,” he told the Guardian. “It did not deter us. It made us fight more.”

Salah Khalaf, a Fatah intelligence chief, was killed in Tunis in 1991. Photograph: Roland Neveu/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images

In the 1980s, Israel continued its assassination campaigns, killing Fatah’s intelligence chief, Salah Khalaf, in Tunis in 1991. Former Mossad officials now say that this may have been a mistake, as Khalaf had recently endorsed a strategy of negotiating a political solution to the conflict between Israel and Palestinians and might have been a more effective successor to Arafat after the leader’s death in 2004.

But others involved in the post-Munich campaign said they had no regrets about any of the killings – contrary to the impression given by the Spielberg film. “We did what we thought was right … and I think it still was right,” said one veteran.

The assassinations continued in the 1990s, as Israel faced a wave of violence from militant Islamist organisations. An effort in 1997 to assassinate Khaled Mashal, one of the highest-profile current Hamas leaders, failed when Mossad agents were caught in Amman after spraying their target with poison. Netanyahu was forced to tell Mossad to hand over an antidote to Jordan in return for the freedom of the detained operatives.

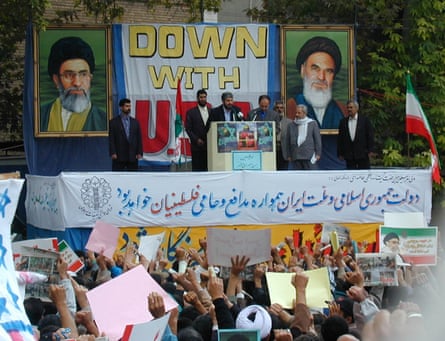

Khaled Mashal (centre, behind microphone, as he gives a speech in Tehran in 2000) was targeted in an assassination attempt in 1997. Photograph: Mohsen Shandiz/Sygma/Getty Images

During the Palestinian uprising from 2000 to 2005, known as the second intifada, Israel stepped up its assassinations.

One of those targeted was Qais abdel Qarim, a veteran leader of the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP). In 2001, a mysterious explosion destroyed much of his home in the West Bank city of Ramallah. The blast came just a week after DFLP militants stormed an Israeli base in Gaza, killing three soldiers.

Qarim dismissed talk of a new assassination campaign against Hamas as a “slogan, not a strategy”. “They are trying to build up support among their population,” he said.

The open question is whether a campaign like the one promised by Netanyahu is actually practicable. The effort after Munich focused on targets in western Europe and Cyprus, but the current Hamas leadership outside Gaza is primarily based in Qatar and Turkey.

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan of Turkey has already warned Israel not to target Hamas officials there, and Alpher said that assassinations would be impossible in Qatar in the foreseeable future. Though the tiny Gulf state hosts Hamas, it is also a key intermediary for negotiations to win the return of about 140 Israeli hostages taken on 7 October by the extremist group and still being held in Gaza.

Should any Hamas leaders escape Gaza into Egypt, Israel would also be unable to reach them there, and assassinations in Europe would now be “inconceivable”, a second veteran of Mossad’s 1970s campaigns said.

“Those days have long gone. The diplomatic damage done in France or the UK or even Germany would be catastrophic,” he told the Guardian.

Efraim Halevy, a senior Mossad official in the 1970s and its director from 1998 to 2002, told the Guardian that force was only effective if used in the correct political circumstances.

“If Hamas emerges as a total loss at the end of the war, then Israel has won the war … but this does not solve the Palestinian problem and the Palestinians will still be around,” Halevy said.

Avner Avraham, an analyst and commentator who spent 29 years in Mossad, said it was obvious that Israel would find and kill those responsible for the 7 October attacks.

“This is the first time we’ve said it [out loud] and we want to do it … for revenge but also to stop people doing the same thing. Is it a useful strategy? Yes. Is it effective? Yes,” Avraham said. “After Munich, one target was killed 20 years later. In this regard, Israel has a memory that is very long.”

Additional reporting by Sufian Taha